Royal Australian Air Force Sunderland Flying Boat of 10 Squadron RAAF bombing a German U-Boat.

(painting courtesy of Australian War Memorial)

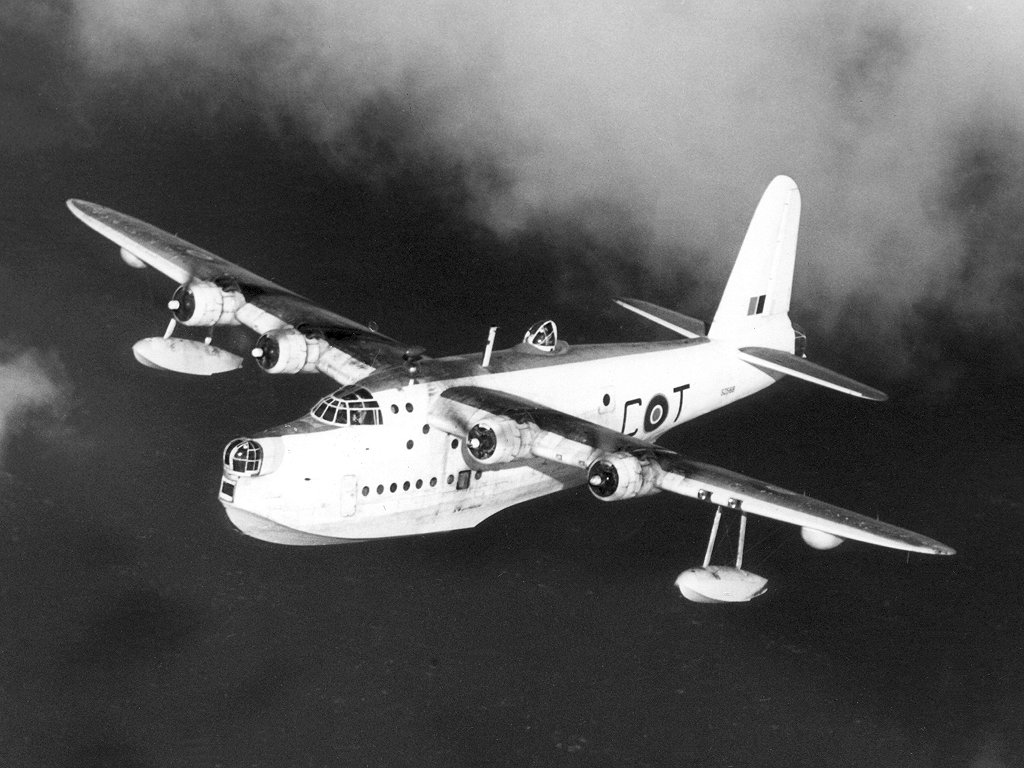

With a crew of eleven, a Short Sunderland Flying Boat could spend 13 hours airborne at a cruising speed of 178 mph (286 km), with a range of 1,780 mi (2,860 km). Short Sunderlands were manufactured by Short Brothers. It isn’t a reference to the length.

Flight engineer of the Royal Australian Air Force, having a smoke, in his bunk on board a Short Sunderland of No. 10 Squadron RAAF stationed in the UK. Given the men flew for as many as thirteen hours, they needed a bit of sleep to stay alert. Sunderland Flying Boats had two decks. The lower deck had six bunks, the galley and the WC. had (Photo by RAF Coastal Command, courtesy of Imperial War Museum, in the public domain).

The men had to eat so someone had to cook which means one of the ratings (or enlisted men) since officers did not perform such chores. A meal being prepared in the galley during an operational flight of a Sunderland aircraft of No. 10 Squadron RAAF. (photo courtesy of Australian War Memorial)

Off duty crew having a meal during a break in their 13-hour patrol

War or no war, someone also had to wash the dishes when on patrol

All the hours of staring at a blank sea made worthwhile: a German Uboat under attack and sunk by a Sunderland of No. 10 Squadron RAAF in June 1942. Crew aboard Sunderland are firing their machine guns to suppress machine gun fire from the U-Boat while making their bombing run. (Photo courtesy of Australian War Memorial).

Sunderland EK573/P of No 10 Squadron RCAF ‘unsticks’ after picking up three survivors from a Wellington shot down in the Bay of Biscay, 27 August 1944. Despite a heavy swell – and the knowledge that many such landing attempts had ended in disaster – Flight Lieutenant W. B. (Bill) Tilley executed a successful rescue. The No 172 Squadron Wellington had crashed after being hit by return fire during an attack on U-534 the previous night. (Caption and photo courtesy of Imperial War Museum, Coastal Command collection, in the public domain)

Comments Charles McCain: On his takeoff run, a Sunderland pilot usually had to rock the plane back and forth to break the surface tension of the water which tended to hold onto the plane. The word “unsticks” in the above caption is a reference to this. Landing in open water was always risky especially if the swells or waves were higher than three feet. Doing so could rip the floats off the wings and cause other damage so the plane could not take off again.

Usually, a Sunderland which came upon survivors in the water would drop a large liferaft or circle the men while ships or RAF Surface Rescue boats could reach them. (Royal Air Force had their own small navy of high-speed rescue boats to pick up downed crews in the English Channel or relatively near the coast). Since the crew being rescued is in the Bay of Biscay, a ship would have been diverted to pick up the men if the Sunderland had not landed.

More than 50% of German U-boats were sunk by Allied aircraft

7 U-Boats Sunk in Bay of Biscay By Allied Air and Sea Patrols; 3 Enemy Ships Go Down in One Battle in Which Sloops Aided — 2 of Total Bag Were Supply Craft for Packs

Headline in New York Times of 7 September 1943

U-boats based on the Channel Coast of France had to transit the Bay of Biscay to get to the Atlantic and as the war went on Allied aircraft were constantly over the bay and sank dozens of U-Boats before they even made their way to the Atlantic. But U-boats began to be fitted with more and more anti-aircraft guns as the war went on.

Says Uboat.net: “More than 120 aircraft and hundreds of men were lost in the fierce battles between the U-boats and their pursuing aircraft. In a number of cases there were no survivors from either the aircraft or the U-boat.”

This is the “go to” site for information about the German U-Bootwaffe. This is a non-political site.

https://uboat.net/history/aircraft_losses.htm

Sunderland patrolling in harsh weather

You can find detailed information on the Sunderland Flying Boat here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Short_Sunderland

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.